The FOMC decided on March 21 to increase the target band for the federal funds rate by 25 basis points, to a range of 1.50-1.75%. This despite inflation running persistently below the Fed's 2% target, only moderate wage growth, and inflation expectations firmly anchored.

What is the FOMC thinking here? To be more precise, what is the dominant view within the FOMC that is driving the present tightening cycle? Remember, the FOMC is made up of 12 regional bank presidents plus 7 board of governors (at full strength) possessing a variety of views which are somehow aggregated into a policy rate decision. I think it's fair to say that the dominant view, especially among Board members, is heavily influenced by the Board's staff economists. So, maybe what I'm really asking is: what is the Board staff thinking?

Perhaps they're thinking along the following lines. Thanks in part to a recent change in U.S. fiscal policy and in part to a relatively robust world economy, the U.S. economy seems poised for a growth spurt of unknown duration. As the economy expands, so too does the demand for investment and credit which, in turn, puts upward pressure on market interest rates. If the Fed does not follow this pressure upward (by raising its policy rate) then it risks inefficiently "subsidizing" investment spending and credit creation (leading to excess credit and spending). There might even be some justification for raising the policy rate more aggressively than what the market would dictate on its own, if it is judged that the imminent growth spurt was due to an "irrational" exuberance or if it is otherwise judged to be unsustainable (and subject to a sharp correction).

The view above may constitute an element of the way a few hawks on the committee are thinking when they cite financial stability concerns. But economists at the Board are probably not thinking exactly in this way because it offers no direct link to the Fed's dual mandate of promoting price stability and full employment. Price stability is interpreted by the FOMC as a long-run PCE inflation rate of 2% per annum. And while there's no official measure of "full employment," for all practical purposes it is defined as a situation in which the unemployment rate is at its "natural" rate.

What is the "natural" rate of unemployment? The Board defines the term

here. According to this statement, it corresponds to the

lowest sustainable level of unemployment in the U.S. economy. How do we know what this lowest sustainable level is? The statement implicitly answers this question by mapping "lowest sustainable level" into some notion of a "long-run normal level" of the unemployment rate. In short, take a look at the average unemployment rate over long stretches of time and assume that it roughly corresponds to what is sustainable. In his recent press conference, Fed Chair Jay Powell explicitly mentioned that any such estimate will a have large confidence interval--that is, we don't know what the natural rate is and we suspect it may change over time. (He might have mentioned that we're not even sure this theoretical object exists in reality but, of course, we could say this of any theoretical construct in economics, including supply and demand curves.)

In any case, here is a plot of the U.S. civilian unemployment rate since 1948, along with the Congressional Budget Office's estimate of the "natural" rate of unemployment:

The unemployment rate does appear to be a relatively stationary time-series. What's interesting about the U.S. data is that the unemployment rate only appears to rise in periods of economic recession (when GDP growth is negative). Moreover, there's evidence of a cyclical asymmetry: when it rises, it rises sharply, but when it declines, it does so relatively gradually (these patterns are not so evident in other countries).

The Board's concern, at present, is the fact that the unemployment rate fell to its (estimated) natural rate of 4.7% early in 2017 and has since declined steadily to 4.1% today. Given a relatively robust global economy, and given the recent fiscal stimulus in the U.S., the unemployment rate is projected to decline even further in the foreseeable future. This, evidently, is bad news. Why? Because it's unsustainable (read: likely to end badly). The economy is presently operating

above its long-run potential level.

What does any of this have to do with inflation?

Inflation is the rate of change of the price level (the "cost of living" measured in dollars). Sometimes people speak of

wage inflation--the rate of change of the average nominal wage rate. Way back in the day, William Phillips noted an apparent inverse relationship between the rate of wage inflation and the unemployment rate. Others noticed a similar inverse relationship between the rate of price-level inflation and the unemployment rate. This statistical relationship became known as the

Phillips curve.

The standard interpretation of the Phillips curve, a version of which is used by the Board staff today, goes something like this: To the extent that business cycles are caused by movements in aggregate demand (e.g., bouts of optimism or pessimism) then one would expect the general level of prices to rise when aggregate demand is high and to decline when aggregate demand is low. Moreover, one would expect firms to recruit workers more intensively when aggregate demand is high than when it is low, so that the unemployment rate should decline in a boom and rise in a recession. In this way, aggregate demand shocks cause unemployment and the price-level to move in opposite directions. One would expect the inflation-unemployment relationship to reverse if a recession was instead triggered by a supply disruption (e.g., an oil price shock).

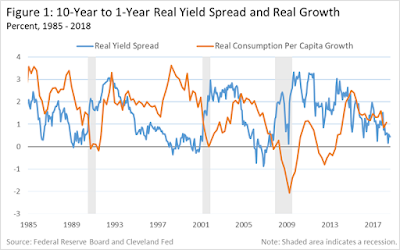

Importantly, the consensus view is that there's no long-run trade-off between inflation and unemployment (or, if there is, it seems to go in the opposite direction). Here's the relationship between inflation and unemployment in the U.S.

Apart from the oil supply shock episodes, inflation and unemployment do tend to move in opposite directions in recessions. But recessions are short-lived, and the relationship between these two variables during economic expansions is much less clear. For example, inflation and unemployment both fell from December 1982 to January 1987, from June 1992 to March 1995, and from August 2011 to October 2015.

It's hard to tell from this data alone whether low rates of unemployment portend higher inflation because in the background we have the Fed raising interest rates when there are signs of inflationary pressure. On the other hand, it's probably just as reasonable to expect the opposite. That is, in a deep demand-driven recession that drives the unemployment rate up and the inflation rate down, the

high rate of unemployment at the trough should forecast

higher future inflation (assuming that inflation is expected to return to target).

Is there any evidence that a low unemployment rate during an expansion forecasts higher future inflation? My feeling is that the empirical evidence is weak on this score. If so, then it is odd that so many people seem to believe that "low unemployment

causes higher inflation." One can see this idea manifest itself in headlines like this:

Fed's Mission Improbable: Lift Unemployment--But Avoid Recession (by Greg Ip of the WSJ). I reproduce a few of the opening paragraphs here for convenience:

Massive tax cuts, robust federal spending and a synchronized global upswing are expected to push annual growth in economic output to 2.7% this year and 2.5% next—past what Fed officials consider its long-run sustainable rate of 1.8%—according to projections Fed officials released after their meeting Wednesday.

To sustain such growth, the Fed projects employers will have to dig deep into a diminishing supply of workers. That will cause unemployment, already at a 17-year low of 4.1%, to sink to 3.6% by the fourth quarter of 2019, a level last seen in the 1960s. That’s well below the “natural rate” of 4.5%, which is the rate Fed officials and many economists think the economy can sustain without eventually producing inflation.

But it faces a problem: In theory, unemployment will eventually have to go back to 4.5%, or inflation will head even higher. Yet since records begin in 1948, unemployment has never risen by 0.9 points, except in a recession.

This

almost makes it sound like the Fed is

trying to increase the unemployment rate. Of course, this is not how Fed officials would describe their intent. The goal is to ensure that the economy does not embark on an "unsustainable" (bound-to-end-badly) growth path. To hedge against this event, the Fed will have to raise its policy rate to keep aggregate demand and inflation in check. The collateral damage in this hedging strategy is for the unemployment rate to rise (hopefully in a smooth manner and to more sustainable levels).

I think it's time for economists to stop relying so heavily on the Phillips curve as their theory of inflation.There are two good reasons to do so. First, it's bad PR to (unintentionally) suggest that workers are somehow responsible for inflation. Second, and more importantly, it would help avoid policy mistakes like raising the federal funds rate too aggressively against low unemployment rate data.

To see the potential for policy mistakes, recall how in December of 2012 the FOMC adopted the so-called "Evans rule" (named after Chicago Fed president Charlie Evans):

In particular, the Committee decided to keep the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this exceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unemployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, inflation between one and two years ahead is projected to be no more than a half percentage point above the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and longer-term inflation expectations continue to be well anchored.

I pointed out

here at the time that while the Evans rule was meant to signal a more Dovish policy, it was inadvertently signalling a more Hawkish policy. As it so happened, the Fed did not raise its policy rate when the unemployment rate broke below 6.5% in April 2014. But it might have, and markets likely hedged against this possibility, resulting in a tighter than desired monetary policy.

In any case, back to the current tightening cycle and the factors influencing it. A few FOMC members are asking what the apparent rush to raise rates is all about. Jim Bullard, president of the St. Louis Fed has long been a vocal advocate for data-dependent policy. Inflation remains below target and long-term inflation expectations are on the low side as well. According to Bullard, the Fed can afford to be patient (and to move rapidly as conditions dictate).

One counterpoint to this view is the idea that the Fed needs to "get ahead of the curve." Again, the notion is that while inflation remains below target, we are confident that it will soon return to target and we can see inflationary pressures building up in the horizon (as evidenced by the very low rate of unemployment, among other things). I saw Charlie Evans push back against this idea pretty effectively on a recent CNBC interview. According to Evans, the "getting ahead of the curve" idea is largely a byproduct of an era where inflation was almost always above target. In the past six years, however, we've been operating in an environment where inflation has been persistently below target. Getting ahead of the curve is perhaps not as pressing an issue as it once was. A doubling of the inflation rate from 1.5% to 3% is not as disconcerting as a doubling from 4% to 8%.

I think that Minneapolis Fed president Neel Kashkari has a pragmatic approach to the problem (see the reasons he gives

here for why he dissented for the 3rd time against raising the policy rate). Suppose we subscribe to the notion that a below-natural-rate of unemployment portends future inflation. Suppose further we admit that we do not know where the natural rate of unemployment resides (as mentioned above, Fed Chair Jay Powell alluded to the uncertainty surrounding this estimate). Well, then why not just assume that the natural rate is declining as long as we see no evidence of price or wage inflation pressure?

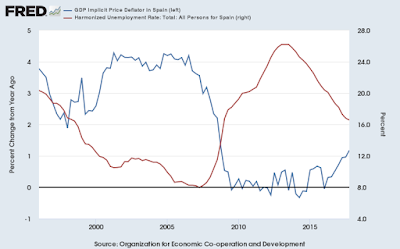

If we abandon the traditional Phillips curve view of inflation, what do we replace it with? I think that the traditional money supply/demand approach provides a firmer foundation for understanding inflation (see

here,

here and

here). In particular, we can expect the price-level to rise as households and firms attempt to dispose of excess nominal wealth balances (as when government debt is issued too rapidly when an economy is near full employment--a situation much like today). Conversely, we can expect the price-level to decline (or inflation to slow down) as the demand for safe nominal wealth rises (as in times of crisis). The framework is perfectly consistent with the Phillips curve, but with the direction of causality mainly reversed. That is, we can "blame" unexpected swings in inflation/deflation (emanating from deeper forces) for influencing the unemployment rate, and not the other way around.